Fault Tolerance in a High Volume, Distributed System

01 Mar 2012Originally posted on the Netflix Tech Blog:

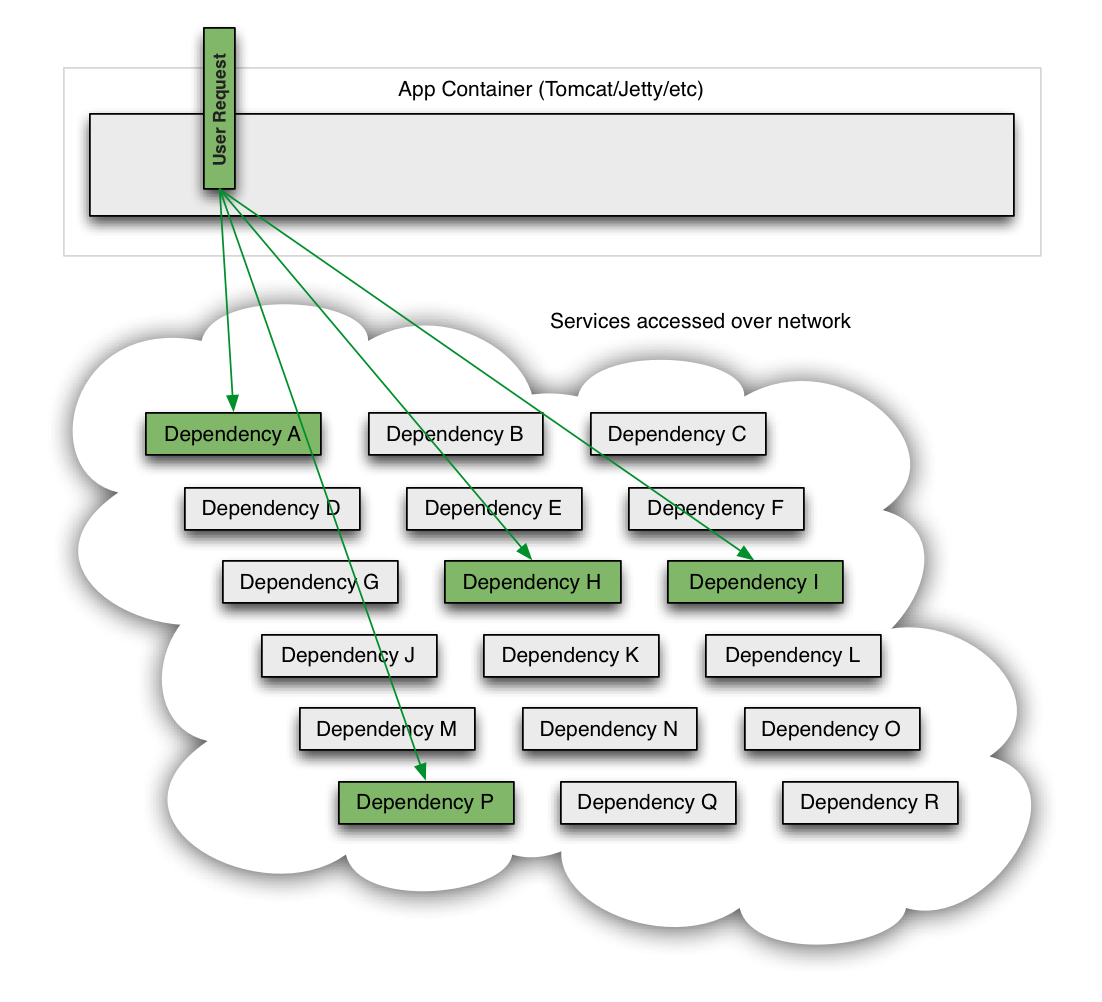

In an earlier post by Ben Schmaus, we shared the principles behind our circuit-breaker implementation. In that post, Ben discusses how the Netflix API interacts with dozens of systems in our service-oriented architecture, which makes the API inherently more vulnerable to any system failures or latencies underneath it in the stack. The rest of this post provides a more technical deep-dive into how our API and other systems isolate failure, shed load and remain resilient to failures.

Fault Tolerance is a Requirement, Not a Feature

The Netflix API receives more than 1 billion incoming calls per day which in turn fans out to several billion outgoing calls (averaging a ratio of 1:6) to dozens of underlying subsystems with peaks of over 100k dependency requests per second.

This all occurs in the cloud across thousands of EC2 instances.

Intermittent failure is guaranteed with this many variables, even if every dependency itself has excellent availability and uptime.

Without taking steps to ensure fault tolerance, 30 dependencies each with 99.99% uptime would result in 2+ hours downtime/month (99.99%30 = 99.7% uptime = 2+ hours in a month).

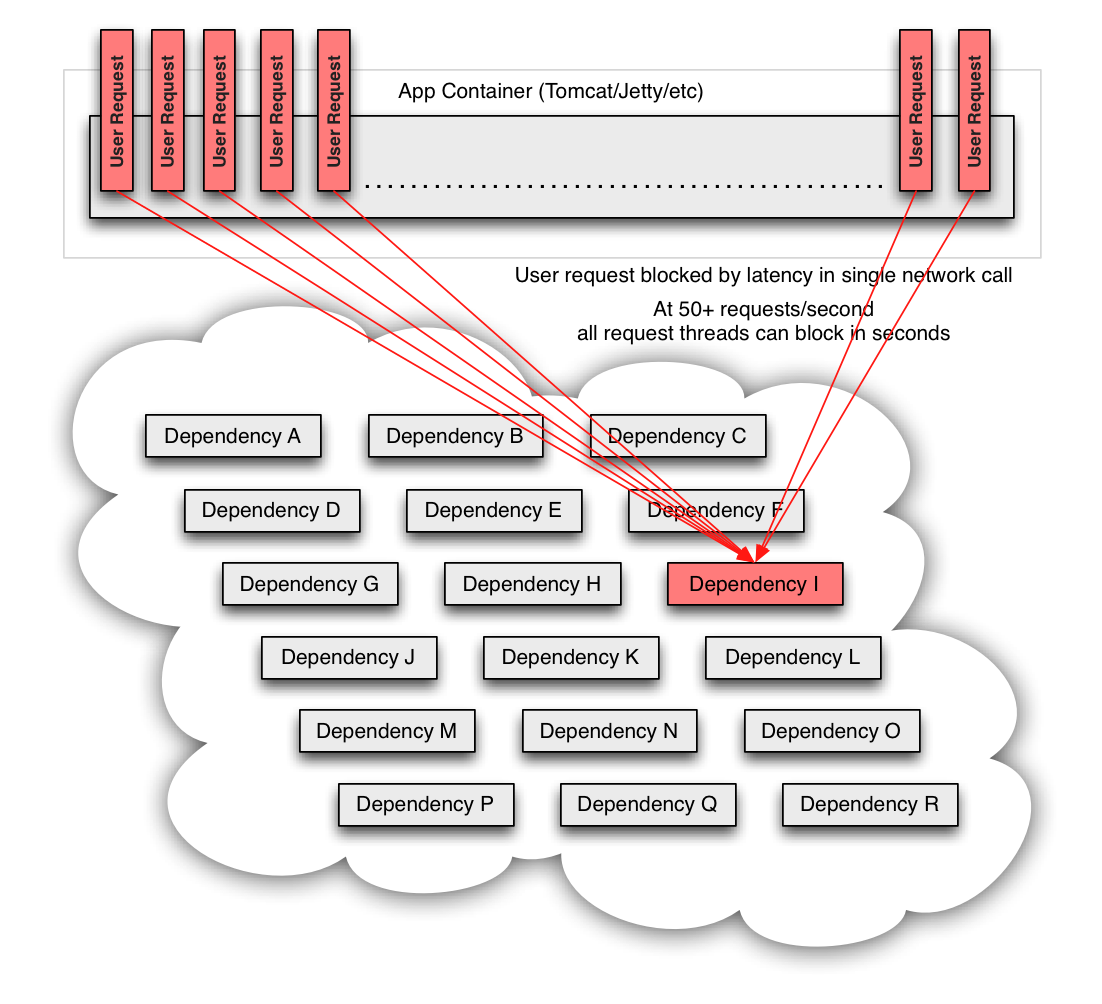

When a single API dependency fails at high volume with increased latency (causing blocked request threads) it can rapidly (seconds or sub-second) saturate all available Tomcat (or other container such as Jetty) request threads and take down the entire API.

Thus, it is a requirement of high volume, high availability applications to build fault tolerance into their architecture and not expect infrastructure to solve it for them.

Netflix DependencyCommand Implementation

The service-oriented architecture at Netflix allows each team freedom to choose the best transport protocols and formats (XML, JSON, Thrift, Protocol Buffers, etc) for their needs so these approaches may vary across services.

In most cases the team providing a service also distributes a Java client library.

Because of this, applications such as API in effect treat the underlying dependencies as 3rd party client libraries whose implementations are “black boxes”. This in turn affects how fault tolerance is achieved.

In light of the above architectural considerations we chose to implement a solution that uses a combination of fault tolerance approaches:

-

network timeouts and retries

-

separate threads on per-dependency thread pools

-

semaphores (via a tryAcquire, not a blocking call)

-

circuit breakers

Each of these approaches to fault-tolerance has pros and cons but when combined together provide a comprehensive protective barrier between user requests and underlying dependencies.

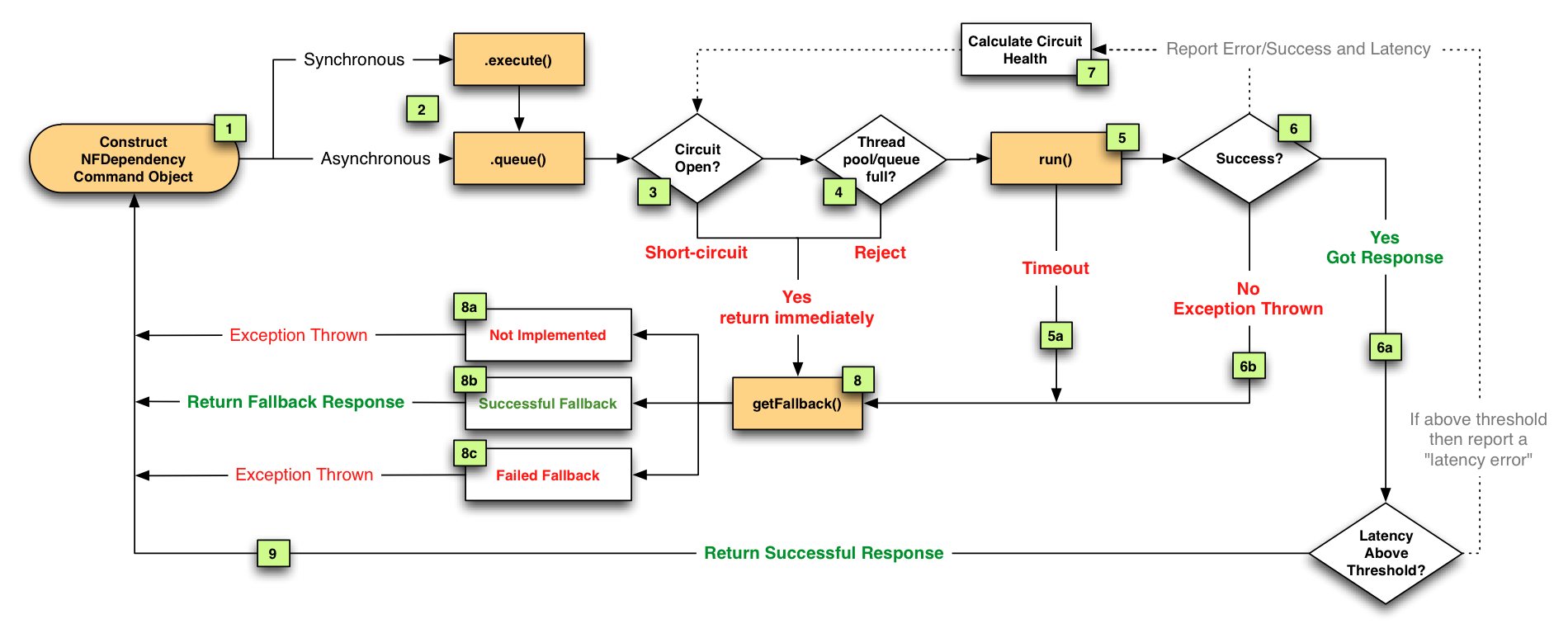

The Netflix DependencyCommand implementation wraps a network-bound dependency call with a preference towards executing in a separate thread and defines fallback logic which gets executed (step 8 in flow chart below) for any failure or rejection (steps 3, 4, 5a, 6b below) regardless of which type of fault tolerance (network or thread timeout, thread pool or semaphore rejection, circuit breaker) triggered it.

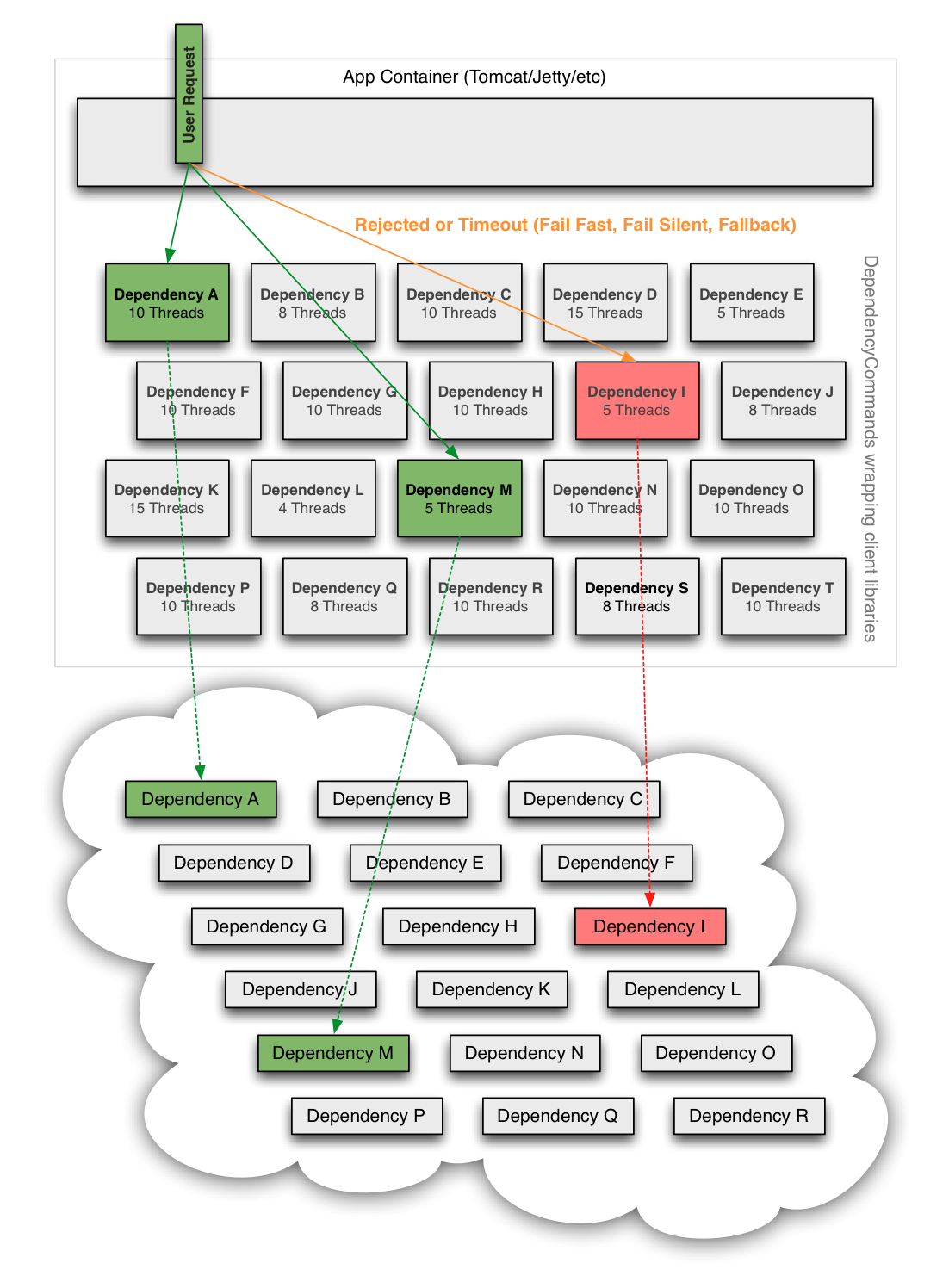

We decided that the benefits of isolating dependency calls into separate threads outweighs the drawbacks (in most cases). Also, since the API is progressively moving towards increased concurrency it was a win-win to achieve both fault tolerance and performance gains through concurrency with the same solution. In other words, the overhead of separate threads is being turned into a positive in many use cases by leveraging the concurrency to execute calls in parallel and speed up delivery of the Netflix experience to users.

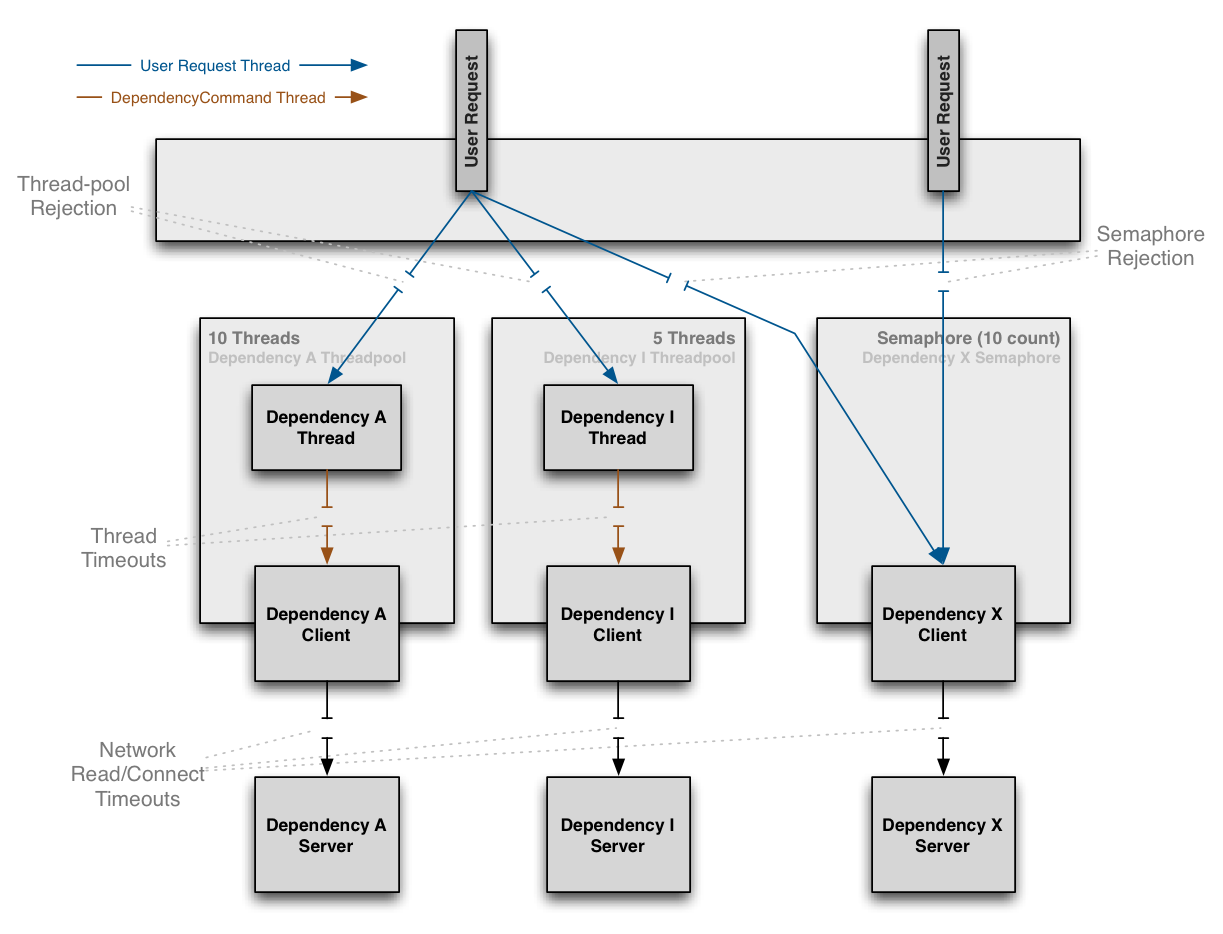

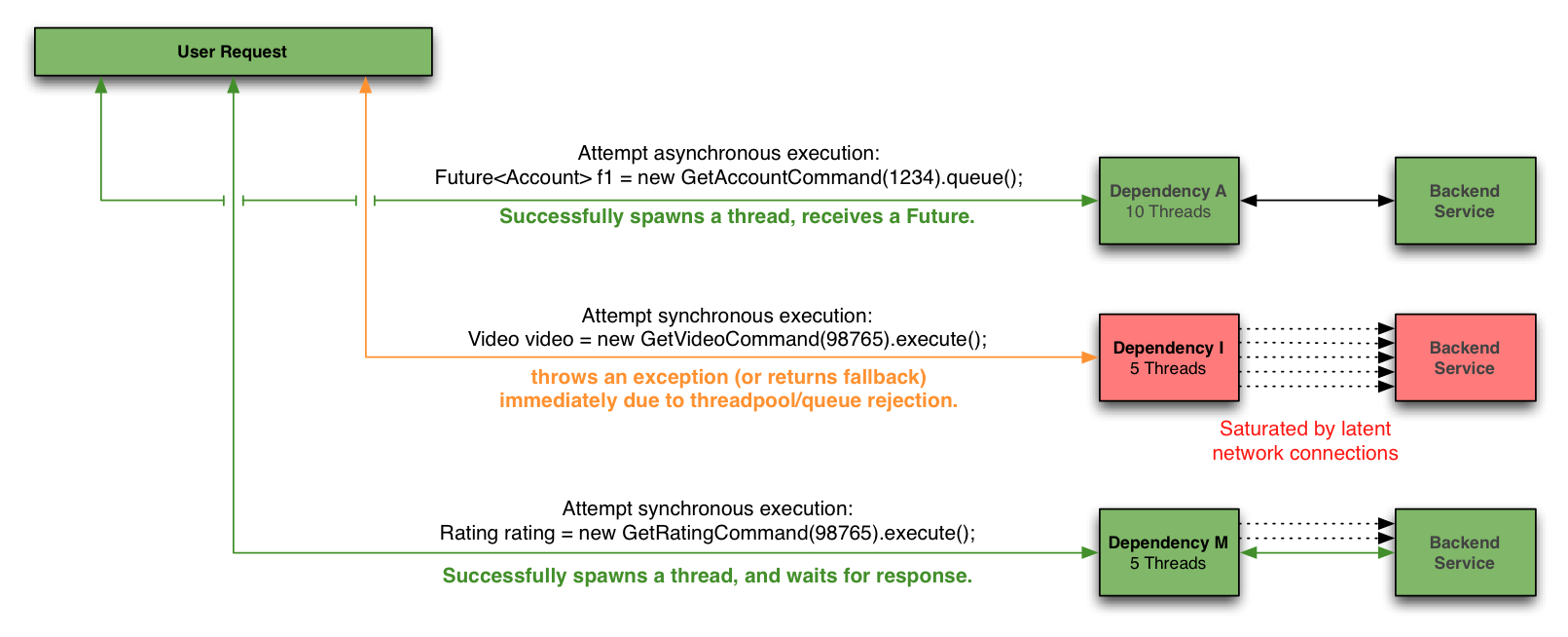

Thus, most dependency calls now route through a separate thread-pool as the following diagram illustrates:

If a dependency becomes latent (the worst-case type of failure for a subsystem) it can saturate all of the threads in its own thread pool, but Tomcat request threads will timeout or be rejected immediately rather than blocking.

In addition to the isolation benefits and concurrent execution of dependency calls we have also leveraged the separate threads to enable request collapsing (automatic batching) to increase overall efficiency and reduce user request latencies.

Semaphores are used instead of threads for dependency executions known to not perform network calls (such as those only doing in-memory cache lookups) since the overhead of a separate thread is too high for these types of operations.

We also use semaphores to protect against non-trusted fallbacks. Each DependencyCommand is able to define a fallback function (discussed more below) which is performed on the calling user thread and should not perform network calls. Instead of trusting that all implementations will correctly abide to this contract, it too is protected by a semaphore so that if an implementation is done that involves a network call and becomes latent, the fallback itself won’t be able to take down the entire app as it will be limited in how many threads it will be able to block.

Despite the use of separate threads with timeouts, we continue to aggressively set timeouts and retries at the network level (through interaction with client library owners, monitoring, audits etc).

The timeouts at the DependencyCommand threading level are the first line of defense regardless of how the underlying dependency client is configured or behaving but the network timeouts are still important otherwise highly latent network calls could fill the dependency thread-pool indefinitely.

The tripping of circuits kicks in when a DependencyCommand has passed a certain threshold of error (such as 50% error rate in a 10 second period) and will then reject all requests until health checks succeed.

This is used primarily to release the pressure on underlying systems (i.e. shed load) when they are having issues and reduce the user request latency by failing fast (or returning a fallback) when we know it is likely to fail instead of making every user request wait for the timeout to occur.

How do we respond to a user request when failure occurs?

In each of the options described above a timeout, thread-pool or semaphore rejection, or short-circuit will result in a request not retrieving the optimal response for our customers.

An immediate failure (“fail fast”) throws an exception which causes the app to shed load until the dependency returns to health. This is preferable to requests “piling up” as it keeps Tomcat request threads available to serve requests from healthy dependencies and enables rapid recovery once failed dependencies recover.

However, there are often several preferable options for providing responses in a “fallback mode” to reduce impact of failure on users. Regardless of what causes a failure and how it is intercepted (timeout, rejection, short-circuited etc) the request will always pass through the fallback logic (step 8 in flow chart above) before returning to the user to give a DependencyCommand the opportunity to do something other than “fail fast”.

Some approaches to fallbacks we use are, in order of their impact on the user experience:

-

Cache: Retrieve data from local or remote caches if the realtime dependency is unavailable, even if the data ends up being stale

-

Eventual Consistency: Queue writes (such as in SQS) to be persisted once the dependency is available again

-

Stubbed Data: Revert to default values when personalized options can’t be retrieved

-

Empty Response (“Fail Silent”): Return a null or empty list which UIs can then ignore

All of this work is to maintain maximum uptime for our users while maintaining the maximum number of features for them to enjoy the richest Netflix experience possible. As a result, our goal is to have the fallbacks deliver responses as close to what the actual dependency would deliver.

Example Use Case

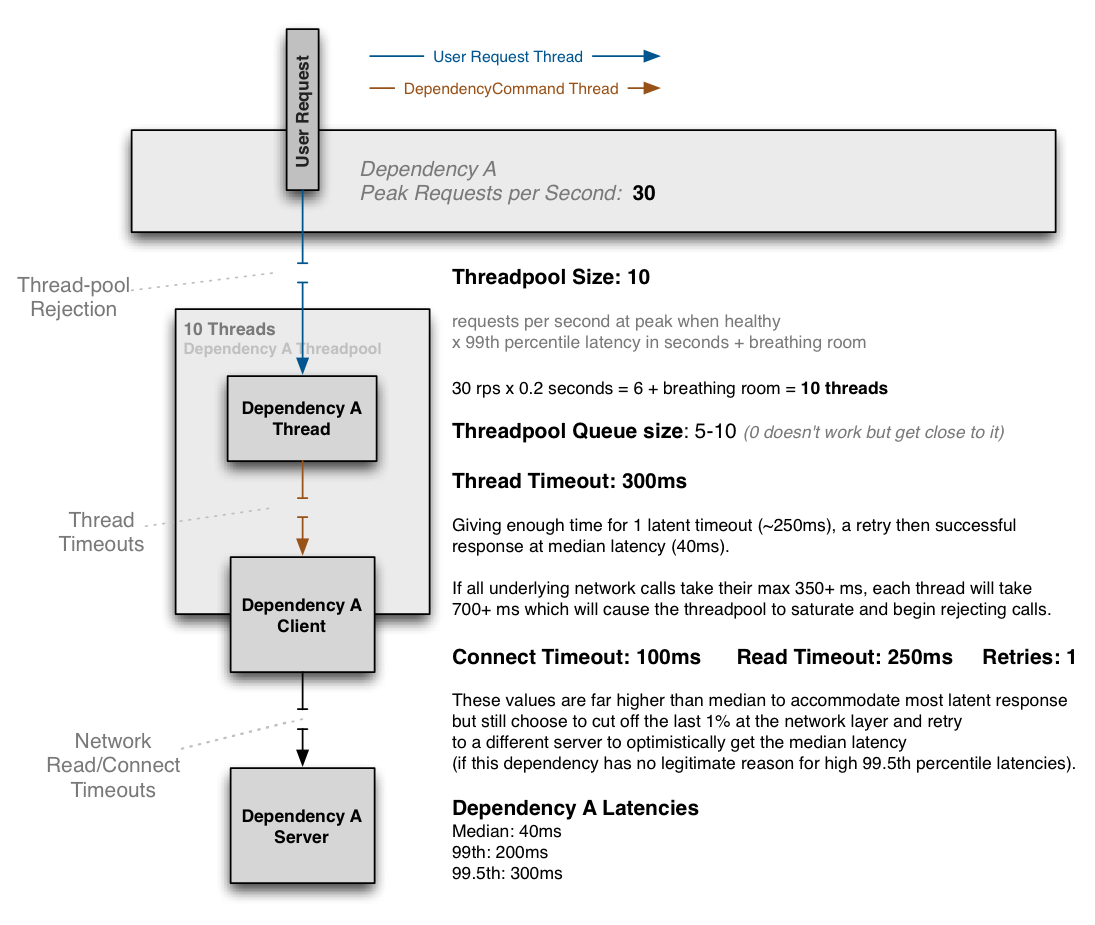

Following is an example of how threads, network timeouts and retries combine:

The above diagram shows an example configuration where the dependency has no reason to hit the 99.5th percentile and thus cuts it short at the network timeout layer and immediately retries with the expectation to get median latency most of the time, and accomplish this all within the 300ms thread timeout.

If the dependency has legitimate reasons to sometimes hit the 99.5th percentile (i.e. cache miss with lazy generation) then the network timeout will be set higher than it, such as at 325ms with 0 or 1 retries and the thread timeout set higher (350ms+).

The threadpool is sized at 10 to handle a burst of 99th percentile requests, but when everything is healthy this threadpool will typically only have 1 or 2 threads active at any given time to serve mostly 40ms median calls.

When configured correctly a timeout at the DependencyCommand layer should be rare, but the protection is there in case something other than network latency affects the time, or the combination of connect+read+retry+connect+read in a worst case scenario still exceeds the configured overall timeout.

The aggressiveness of configurations and tradeoffs in each direction are different for each dependency.

Configurations can be changed in realtime as needed as performance characteristics change or when problems are found all without risking the taking down of the entire app if problems or misconfigurations occur.

Conclusion

The approaches discussed in this post have had a dramatic effect on our ability to tolerate and be resilient to system, infrastructure and application level failures without impacting (or limiting impact to) user experience.

Despite the success of this new DependencyCommand resiliency system over the past 8 months, there is still a lot for us to do in improving our fault tolerance strategies and performance, especially as we continue to add functionality, devices, customers and international markets.